Imagine this. You’re grabbed out of your home, stuffed into a box, thrown in a car, and driven to a location where you’re left in a strange room. It’s a room with alien smells, screams that sporadically pierce through the walls, and eerie figures wandering about. You don’t know why the human you once trusted brought you, but you’re not sure you should trust her to help you now.

Every day, pets are brought to our hospitals in this state of confusion and fear and we expect them to remain calm and cooperate for procedures. We poke them and prod them and carelessly flop them into various positions when they have no clue what we want. Then, in the name of speed, we react to the struggling pet by imposing some type of “death grip” hold instead of taking a step back and evaluating whether a more thoughtful approach might work better.

What’s the Harm in Handling Pets the Way We Always Have?

Many participants in this typical scenario might ask, “What’s the harm. It’s what we’ve always done.” Well, the harm is three-fold. First, dog and cat bites, as well as cat scratches, are the top causes of veterinary hospital injuries. According to Hub international, insurance broker for Professional Liability Insurance Trust (PLIT), claims from 2006–2008 averaged $1200.00 per cat injury claim and $1500.00 per dog injury claim. Force-based techniques and crude handling skills undoubtedly play a significant role in these statistics.

Second, for those of us who vowed to first “Do no harm” as a veterinarian—every time we force pets in this manner or even handle pets in a rushed, careless way, we risk breaking this promise. We may send the patients home medically better, but they may also be leaving with a “behavioral broken arm.” That’s because a bad experience on one visit can make them worse for the next. With each experience their difficult behavior and fear can grow worse until they are no longer treatable by a veterinarian. Even more ominous is the fact that a bad experience at the veterinary hospital can cause some pets to be worse with people overall. For an animal that comes in and is already slightly fearful of unfamiliar people or who has a genetic predisposition towards this trait, one bad experience can throw them over the edge from a dog that’s just fearful of some people to one who has a generalized and pronounced fear or suspicion of anyone new. Or worse, one that is no longer fearful but is now fear aggressive. And the veterinary staff could be the inciting factor that triggers this dramatic turn for the worse, which ultimately can contribute to the decision to euthanize.

A third source of harm in rushed or unskilled handling is to the credibility of the hospital staff and the perception of how caring they are. Imagine if you took your child to a dentist. Which would you chose? The one who was in a rush and strapped your screaming child down in order to get the job done, or the one who set up the hospital to look inviting and knew just the right words to say to put your child at ease? The first dentist would be seen as cold and concerned most about money. The second would be seen as caring about the child, more skilled at handling children, and as being more credible. Now imagine what’s going on in the child’s mind. The restrained child is likely to have a lifelong fear of seeing a dentist and, as an adult, may no longer seek dental care. The parents would also be less apt to bring child 1 back for regular appointments because they, too dread the process due to it’s effect on the child and the embarrassment of having others see their child’s difficult behavior. On the other hand, the child that went to the child-friendly dentist would become increasingly easier to treat and her parents more likely to keep up the regular visits.

The Solution: Set up the Hospital and Handling to Help the Patient Feel Comfortable and Safe

One might think that switching from the status quo of powering through procedures to a low stress handling and hospital environment would take an impractical amount of effort and waste precious time. In reality, many of the changes are a matter of setting up a more inviting hospital. Others are a matter of approaching animals correctly and learning to handle them or support them in ways that they feel comfortable and safe. As a result, the changes often don’t take more time; they just require more skill. For cases where more time is needed to train pets that the procedures and environment are safe, this time can be turned into a value-added service that is carried out by technicians and assigned an appropriate fee. It’s something that does not have to be sold to the client, just offered as part of the best practice—just like pre-anesthetic blood work or heartworm testing. Owners can be informed of their options and the potential consequences.

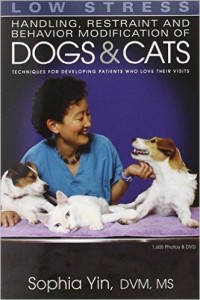

In general if we provide an environment where the animal feels comfortable and safe while also providing clear guidance regarding what we want the animal to do, the pet will be less fearful and more cooperative which in turn will help us get through the procedures more quickly both now and on future visits. Here are six tips to setting up a veterinary hospital (or groomer) as a pet friendly practice while actually increasing hospital efficiency. For a more detailed description and techniques refer to the book and DVD set: Low Stress Handling, Restraint and Behavior Modification of Dogs & Cats (CattleDog Publishing, www.lowstresshandling.com). The six steps are as follows:

Tip 1: Before the Patient Comes in: What the Owner Can Do At Home

Train the pet to love being in a crate and enjoy car rides so that the precursors to the actual visit are fun.

Tip 2: Preparing The Hospital

The hospital should be a calm, relaxing place. Have separate dog and cat waiting areas and many visual barriers within each section. That way, animals that are afraid of other pets don’t have to be face to face. Place towels or rugs on the foreboding metal scales so dogs aren’t faced with a scary weighing task even before the potentially scarier part is to come.

Tip 3: Greeting the Pet Appropriately

The pet’s first impression of the hospital is based, not only on the environment, but on how people interact with them, especially upon first greeting. Probably the number one reason people get bitten by unfamiliar dogs is that they approach the dog incorrectly. Staff approach too quickly, crowd too closely or loom over them. Under this pressure some dogs will freeze, cower, or flee. Others will defend themselves. Staff should instead greet by standing sideways and getting down at the dogs level while averting their gaze. They can also toss tasty treats at a fast rate inconspicuously so the pet associates them with good thing.

Tip 4: Handling the Pet in a Calm Skilled Manner

Once we have greeted the pet correctly and made a good first impression. It’s important to know how to handle him in a way that guides him into the positions you want rather than in ways that cause him to become confused. For instance, if we want to have dog change positions from standing to lateral and you do so in a manner that causes them to struggle and hit their head, they may be less likely to allow us to guide them in other position changes.

From Low Stress Handling, Restraint and Behavior Modification of Dogs & Cats by Sophia Yin, DVM, MS.

From Low Stress Handling, Restraint and Behavior Modification of Dogs & Cats by Sophia Yin, DVM, MS.

Tip 5: Desensitization and Counterconditioning the Fearful Pet

When all of the above steps are followed, clients will notice a huge difference. But one huge addition to your practice is the technique of desensitization and counterconditioning. This is where you change the pet’s emotional state to happy in the setting or for the procedure where he was fearful before. You can do this by pairing the situation or procedure with something good like tasty treats. And the entire process goes much faster if you start with the scary issue far away or at a low level and only increase the level when the pet looks relaxed and happy. For instance, if the dog hates getting injections you could put cheese whiz on a syringe. Then you could pair feeding treats with pinching the skin, then pinching the skin more vigorously, then poking the skin with the capped syringe, and then finally actually giving the injection. This process can takes as little as a minute in some dogs who were very reactive previously.

Tip 6: Note that some animals will need chemical restraint and it’s best to give the injectable sedatives before they reach a high arousal level. However it should still be combined with the tips above.

Take-home Message

Overall, by focusing your hospital’s practices around keeping the patient both comfortable and feeling safe, we get back to the roots of veterinary practice. It’s about helping pets to be healthier and happier while forging a great relationship with both patients and client.