Cat treats

Cat treats. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Chances are, at some point in your cat’s life, they are going to need medications. Making sure your cat receives this medication can be challenging and stressful. Transdermal medications, which are applied to the inside of the ear flap, are not always ideal or effective, while liquid medications tend to cause a mess. Then there is the question, “Did my cat actually ingest any of it?”. It is often hard to know how much medication actually made it into the cat and how much is on your shirt.

There are many different ways to “pill” a cat. Some methods use force, while others involve trickery and bribing. You can wrap your cat in a towel and pry open their mouth, stick a pill down the back of their throat, and chase the pill with water to get them to swallow.

Other methods include using a pill gun to avoid manually opening their mouth, crushing the pill, or opening the capsule to mix with food. However, no methods guarantee your cat will safely and effectively take their medication.

You may notice they are now actively avoiding you or, even worse, trying to scratch or bite in self-defense. This leads to the question: What if your cat willingly ate medications from your hand? Or came to you to “ask” for more? Would you believe this can be a reality? All it takes is a little bit of flexibility, ingenuity, and preparation.

Here Are a Few Useful Tips on How to NOT Pill Your Cat:

Method One:

This is an easy one. Find something you can easily hide a pill in, such as a pill pocket, piece of lunchmeat, baby food, Churu®, or cheese. It doesn’t have to be anything special, just something you know your cat will eat, no questions asked.

Coat the pill and feed it to your cat from your hand, in their bowl, or even try “accidentally” dropping it on the floor- oops!

Method Two:

What if there was a way to get your cat to come to you willingly to take their medication? That would be amazing! To make this dream come true, it all starts with a mat. Just like dogs, cats can easily learn how to station on a mat using positive reinforcement techniques. This behavior is not hard to teach, but it takes some time, a little bit of skill, and preparation. If you start when your cat is young, chances are this is a behavior they will remember for life.

If your cat is older, don’t despair, they can still learn. It may take a little more time for your cat to figure out what causes the treats to appear and how to keep them coming once they start. But once your cat figures out the game, it will be easy to slip a pill into one or more of the treats. Chances are they will gobble it up like the rest without a second thought.

If you don’t have the time or desire to teach this behavior, you have another option. Use a non-slip bathmat and either bring it to your cat or have them come to you. Which method you choose doesn’t matter, but if you are electing to have your cat come to you, make sure you are consistent in the location.

Bring the bathmat out twice a day and give your cat three special treats on this mat every day. Once again, make sure it is something you know your cat will eat. Offer treat number one, followed by treat number two, then quickly follow up with treat number three. The goal would be to place the medication in treat number two eventually. Make sure to put the special mat away after your cat finishes their treats and walks away.

Method Three:

This method is a variation of method two but adds in a lickable mat. You can place the lickable mat on the non-slip mat or just use the lickable mat by itself and follow method number two.

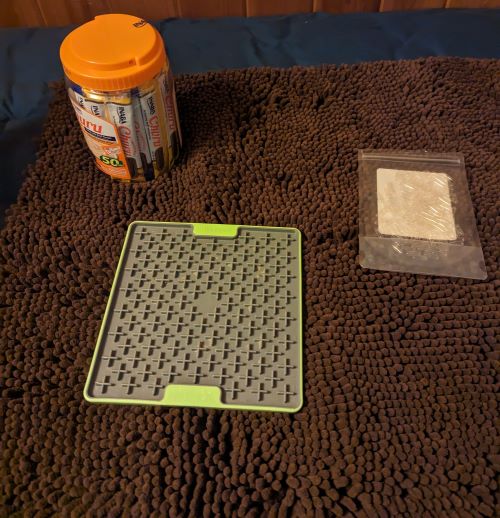

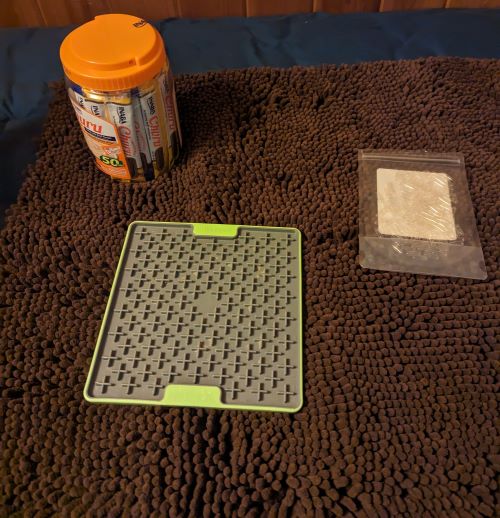

Cat treats. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Lick mat. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Method Four:

What happens if your cat is suspicious about medications? Did you know that you can purchase empty gel caps and hide your cat’s medication in them? Depending on the size, you may even be able to hide multiple medications all in one.

Lick mat. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Lick mat, empty gel cap, and cat treats. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Example of an empty gel capsule. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

In this situation, the process is the same as above, but first practice giving your cat an empty gel cap on their mat before adding the tablet or tablets. If you don’t mind the mess, you may find that your cat will eat the gel cap directly out of your hand. No questions asked!

Assorted gel caps. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Gel cap. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Medication hidden in a treat. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

You can also use these methods to carrier train your cat. Again, start early to get your cat comfortable with the process before you need it, and instead of bringing the carrier to your cat, leave it out in an area where they like to spend time during the day. Do this well in advance of your departure (weeks to months) so it doesn’t raise suspicion or cause your cat to flee. Every day, place the lickable mat with special treats inside the carrier, just like methods two and three outlined above.

Your cat might eat the gel cap directly from your hand. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Tiny amount of medicine. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

These are just a few ways to medicate cats using Low Stress Handling® methods. No fight, no stress, and no pain. Just a yummy snack to make your cat’s day.

Make it interesting. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB

Medicine gone, no questions asked. Photo Courtesy Christine D. Calder, DVM, DACVB