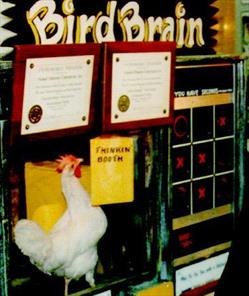

I went through the picture in my head. Chicken number one climbs up the ladder onto a one-foot-wide platform, makes a 180-degree turn and tightropes across a narrow bridge to a second platform, where it pecks a tethered ping-pong ball, sending the ball in an arc around its post. The chicken then turns 180 degrees and negotiates a second ladder back down to ground level, where it encounters a yellow bowling pin and a blue bowling pin in random arrangement. It knocks the yellow one down first and then the blue one.

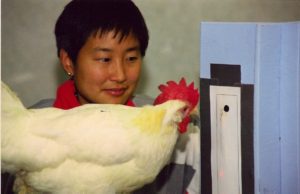

Chicken number two grasps a loop tied to a bread pan and with one continuous pull drags the pan two feet. Then, in a separate segment, it pecks a vertical one-centimeter black dot on cue and only on cue three times in 15 seconds. The cue is a red laser dot.

Scenes from a Saturday morning cartoon? A twisted scheme of some sort? Neither of the above. It’s the assigned mission at the August 2000 Advanced Operant Conditioning Workshop (a.k.a. chicken training camp), taught by Bob Bailey and psychologist Marian Breland-Bailey. Nine animal trainers from the U.S. and Canada, including myself, are here to meet the challenge. We have five days. Sounds like a joke, but it’s serious business. We’re here not just to train chickens. We’re here to learn the intricacies of a universal mechanism of learning called operant conditioning.

Elucidated in the early 1900s by psychologist B. F. Skinner, this theory says that if you reinforce a behavior, it’s more likely to occur again. If you don’t reinforce it, it’s less likely to occur again. Says Marian Breland-Bailey, “Animals are learning all the time, not just during training sessions. And they’re learning with the same principles. Operant conditioning is the way that behavior changes in the real world.” As experienced trainers, we know this. We hope that with a better grasp of the principles of operant conditioning, we can catapult ourselves to a new level of training.

The nine of us form a diverse group. Some train animals professionally for theater or advertising, some have competed avidly in canine obedience trials or have been dog training instructors for years and others just enjoy training their own assortment of pets. Despite our varied backgrounds, we all envision the myriad of benefits these five days will bring forth. When we’re finished we’ll return home to train our clients’ animals more efficiently, to accomplish more with our own pets and to instruct our students more proficiently.

For Marie Gulliford, who has trained everything from cockatoos to pigs, horses, and cows, one of the greatest benefits will be in her grooming shop. “I train the dogs who come in for grooming for my own benefit. My grooming shop is a business for profit. It’s much more profitable if you can groom the dog quickly and it’s easier to do that on a dog that behaves well than on one that’s doing all sorts of extraneous behaviors such as jumping off the table or biting you.”

It’s no accident that we’ve chosen this particular training camp to help us fulfill our training goals. Sue Ailsby, a retired obedience and conformation judge who’s been training dogs for 38 years, expresses the group sentiment: “This course offers an absolutely unique blend of scientific facts and practical applications thereof.” Ailsby, who’s trained dogs for every legitimate dog sport and competed in most of them, and who’s also trained a number of service dogs including her own, frequently lectures at training, handling and conformation seminars. With her years of experience, she’s chosen to train here because, “the Baileys do it better, they do it faster, and do it with a deeper background.”

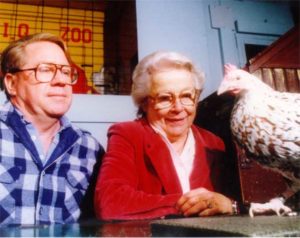

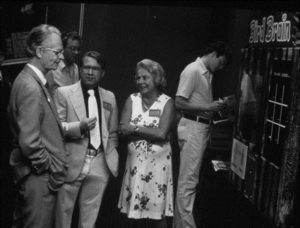

A number of factors sets the Baileys apart from other experienced trainers. The fact that between the two of them Marian and Bob represent 103 years of training, and have trained over 140 species of animals, is impressive in its own right. However, their contributions, especially Marian’s, to the field of animal training extend well beyond numbers. Marian and her now-deceased first husband, Keller Breland, were at the forefront of operant conditioning when it was a relatively new area of study. They were among B. F. Skinner’s first graduate students in the early 1940s. In an odd twist of fate, their studies were interrupted by World War II when Skinner took a hiatus from his university research and instead worked for the U.S. Navy on a project training pigeons to guide missiles. He enlisted Marian and Keller to help, and it was during this project that the two gained invaluable practical experience with the most advanced principles of operant conditioning—aspects they’d read about in their studies but never seen in action.

Surprisingly, it was the simpler principles that convinced them to make animal training a career. Principles such as behavior shaping, whereby you start with a simple behavior that the animal readily offers and gradually reinforce behaviors that look more and more like your goal behavior.

“Skinner had a push button in his hand and had the electronic feeder outside of the training box,” says Marian, recalling an incident during the pigeon bomb guidance project. “At one point he took one of the pigeons outside of its training box and worked on shaping its response because for some reason the pigeon was not pecking its target. So Skinner demonstrated the shaping process. It was then that Keller and I realized how powerful this system was. And we were very excited about it. We decided that after the war we would get into something where we could apply this.”

Since neither had gone on to get a clinical degree they knew they couldn’t get into the treatment of people using this technique. But since they both liked animals and were familiar with different kinds of animals, they decided to go into the animal business.

They started Animal Behavior Enterprises (ABE), a company whose goal was to demonstrate a better, scientific way of training animals in a humane manner using positive reinforcement. They started with dogs, thinking that with so many untrained dogs in the U.S. they’d just demonstrate their new humane way of training and people would begin coming in by the thousands. Says Marian, “We thought it would be a cinch.”

Well, the training part was, but unfortunately, the idea was too advanced for its time. Trainers shunned the new method, claiming that people had been training dogs for centuries already.

Undaunted by this obstacle, Marian and Keller instead headed in a different direction. For 47 years, ABE mass-produced trained animals for its own shows and for animal shows across the country. At their height, the Brelands were training about 1,000 animals at a given time for companies such as General Mills. They also worked on animal behavior research and training projects for groups such as the U.S. Navy and Purina, as well as at Marineland of Florida and Parrot Jungle, where they developed the first of the now traditional dolphin and parrot shows. Through it all, they kept rigorous data on all of the training sessions and published several landmark papers in respectable scientific journals.

During their 47 years, they made a number of important contributions to the animal training world. Says Marian, “One contribution was to give the science of behavior to animal trainers. To encourage the use of operant conditioning behavior analysis in many fields of animal work: in medical behaviors for animals, husbandry behaviors, show behaviors. Just a large number of fields have taken up the operant methods and have used them quite successfully. We’ve been quite gratified by this.”

In fact, the methods have become so ubiquitous that trainers have forgotten where the methods originated. Says Bob Bailey, “There’s one area that I think has been overlooked for a long time and that is that it was the Brelands, even beyond Skinner and the other psychologists, who realized the significance and widespread application of the bridging stimulus. That it would be a revolution in animal training. They recognized it as absolutely key to the widespread training and this was back in 1943.”

And they were right. The bridging stimulus, usually a whistle or a click from a toy clicker, is now used in virtually all marine mammal shows and in training of zoo animals for husbandry behaviors. And, over 40 years after the Brelands first introduced it for use in dogs, it’s finally taken off in the dog training world in the form of clicker training.

We use clicker training with the chickens too. In the beginning operant conditioning workshops, our chickens are trained that a click means food is coming. Now we use the sound to bridge the gap between the behavior we want and the food reinforcement. The bridging stimulus allows us to tell the chicken precisely when it’s doing something right.

While few of us will ever train a chicken again, there are many reasons beyond novelty why we use chickens in this workshop. For one, chickens are so quick that our timing has to be right on. The timing required to train the average dog won’t hack it with chickens. A fraction of a second off and you get a chicken who pecks the red cue dot instead of the black target, or who shakes the loop attached to the bread pan rather than pulling it, or who grasps the ping-pong ball rather than pecking it. Secondly, chickens are particularly skillful at telling us that we need to up the rate of reinforcement. Failure to do so and our fowl friend is running around on the floor in search of food instead of up on the training table learning her tasks.

And the benefits go on. Says Bob Bailey, “A chicken is the best teaching tool for training animals, offering more behaviors and more repetitions in the shortest amount of time.” More repetitions means we can train more behaviors in a short amount of time, and we have more chances to recover from our training blunders.

Yes, even though we’re in the advanced class, we still make our share of mistakes. The difference is that now we know within several five-minute sessions when we’ve made a mistake. Every session we take notes. How many times did we reinforce the chicken for the correct behavior? What percentage of time did the bird offer the correct behavior? By keeping these records we can make better decisions on when to expect more from our bird and when we’ve messed up.

Now, where we would have attributed slow learning to the dim-witted chicken, we instead look for our errors in timing, rate of reinforcement, or consistency. Are we always reinforcing the exact same behavior or do our criteria change from trial to trial thus confusing the chicken? We also record the number of times we reinforce the wrong behavior. A few of these in a row and we’re back to square one. It’s an uphill battle for us, but we’re determined to get the most out of it. And we do. On day five, after a total of 60 to 90 minutes of training per chicken per day, we’ve done it. It’s a room full of poultry performing on cue like pros. Up the ladder, turn 180 degrees, across the bridge, peck the ping-pong ball, turn 180 degrees, down the ladder and then whap! whap! First the yellow bowling pin, then the blue. Click! Treat! Voilà! A flock of trained chickens and nine happy trainers.

Definitions

Classical or Pavlovian conditioning is learning by association. When you repeatedly pair a neutral or “meaningless” stimulus (meaningless to the subject) with a stimulus that innately triggers a physiologic response, the neutral stimulus gradually starts triggering the same physiologic response as the innate stimulus. For instance, dogs automatically salivate when they eat food. If you repeatedly sound a bell immediately before feeding, the dog will associate the bell with food and will soon start drooling when he hears the bell, even in the absence of food. Operant conditioning is learning by trial and error. If an animal’s behavior leads to a reward—such as food—the animal is more likely to repeat the behavior. If the behavior results in an aversive consequence—such as pain—he is less likely to repeat the behavior. Bridging stimulus is a stimulus that bridges the gap in time between a behavior and its consequence. For instance, if you classically condition a chicken to associate a clicking sound with food, you can use the clicking to reinforce good behavior. The click tells the bird that food’s coming. The advantage of using a bridging stimulus is that the trainer can mark the correct behavior precisely so that the animal knows exactly which behavior earned the food reward.

Marian passed away in September 5, 2001. She is survived by Bob Bailey. Chicken training camps are now run by Terry Ryan at http://www.legacycanine.com/workshops

This article first appeared in the Bark in 2000. I’ve reprinted it here to help remind people where and how the science of learning began to trickle down to animal trainers.