Have you ever thought you were pretty brilliant, or at least above average at some common skill only to find out, after taking a test, that you were practically incompetent at that task? Well, that’s what I just found out about my three year old Jack Russell Terrier, Jonesy and his foster dog side-kick, Homer, a couple of years ago when I tested them on a two-choice task to see if they could understand pointing.

According to a research study by Gabriella Lakatos and her colleagues at Eötvös L. University (Budapest, Hungary), dogs are able to recognize the significance of pointing and have the ability to do so similar to a 2-year old child. In this study, the researchers took 15 dogs, 13 two-year-old kids, and 11 three-year-old children and put them through a similar test.

Pre-training the dogs and kids to find a reward in one of two bowls

For dogs, two bowls (brown plastic flower pots: 13 cm in diameter, 13 cm in height) were placed 1.3–1.6m apart, in front of a person on the floor. For kids, the bowls were placed on chairs. The experimenter, in the presence of the dog or kid, placed a reward in one of the bowls: food for the dogs and a favorite toy for the children. The subjects could witness this waiting from a distance of 2–2.5 m with their owner/parent standing behind them. After having the experimenter put the food/toy into the bowl, the owner/parent allowed the subject to take the reward out from the bowl. One trial lasted 30 seconds, and the procedure was repeated twice for each bowl to ensure that the subject knew that the bowls might contain some reward.

The Basic Experiment

Once this was performed they went immediately to testing where the set-up was the same, but the subject didn’t get to see which bowl had the food. The experimenter stood 0.5 meters back from the middle line between the two bowls facing the subject at a distance of 2–2.5 meters. The owner/parent held the child or dog back gently until the experimenter gave the cue. The experimenter got the child’s or dog’s attention, and when the child or dog was looking at the experimenter’s face, she pointed towards the bowl with the food. The child or dog was then allowed to choose only one of the bowls. The other was removed if the dog or child made the wrong choice

The researchers performed two experiments.

Experiment 1: Pointing with the Arms

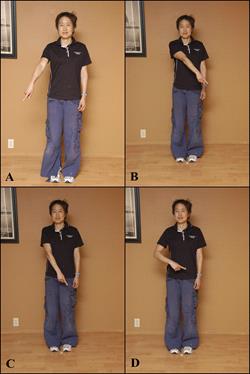

In the first one they compared four types of pointing.

- Distal pointing (Figure A): the experimenter pointed by extending both the arm and finger away from her body and in the direction of the bowl for 1 seconds and then putting her arm back down by her side. Theoretically, this should be the easiest to interpret because the arm is clearly extended away from the body.

- Long cross-pointing (Figure B): This is the same as forward cross-pointing except that her index finger does protrude from her silhouettes.

- Forward cross-pointing (Figure C): Again some part of her arm is crossing her body. This time her arm is straight but point across her body to the bowl with the food. Her hand does not extend past her silhouette.

- Elbow cross-pointing (Figure D): in this case, the elbow is bent such that the experimenter’s elbow is facing the bowl that has no treat but her hand and index finger are pointing towards the bowl with the food. Her elbow extends outside her body but her pointing hand does not extend past her midline.

Results

What were the results? Well, in all cases, the 3-year-old children performed better than the 2-year-olds, who performed better than the dogs. But, at least, dogs were able to interpret pointing correctly more often than not when the pointer’s index finger extended past the body—e.g. distal pointing and long cross-pointing. And in the case of the elbow cross-pointing, they tended to go to the side the elbow was pointing (although barely).

Overall the dogs’ performance was not stellar

- About 80% of the time they went to the correct bowl if there was distal pointing.

- Around 70% of the time they went to the correct bowl with long-cross-pointing.

- About 65% of the time they went to the bowl where the elbow pointed (rather than where the index finger pointed) with elbow cross-pointing. That’s not necessarily that much more than the 50% correct answer they would have with chance. That is, if you were taking a true-false test and just guessed, you would be likely to get 50% correct by chance.

Performance of children

- 3-year-old children got the pointing answer correct about 100% of the time.

- 2-year-old children went to the right bowl about 90% of the time in all cases where the pointers arms were straight.

- 2-year-old children had problems knowing where to go when the elbow pointed one way and the index finger pointed another though and performed similarly to dogs here.

Experiment 2: Pointing with the Legs

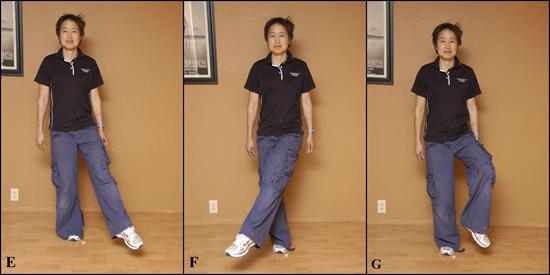

In Experiment Two, the researchers wanted to see if the children and dogs could generalize to a different type of pointing cue—pointing with the legs.

- Pointing with the leg that was closer to the bowl (Figure E)

- Leg cross-pointing with the leg further from the bowl (Figure F)

- Pointing with her knee (Figure G)

- As a control they also used distal hand pointing

Results

Again, 3-year-old children performed the task correctly nearly 100% of the time. Everyone performed the distal pointing, pointing with the leg, and cross-pointing with the leg better than chance, but only at 65–70% correct for dogs (e.g., barely more than compared to chance). Two-year-olds consistently performed better than dogs but, neither dogs or 2-year-olds understood the knee-pointing.

Overall study conclusion:

Overall, the researchers concluded that 3-year old children are more advanced than 2-year-olds and dogs in terms of their ability to interpret pointing with the hands as well as gesturing with other body parts to locate a hidden object. And they understood to focus on the hand and index finger in particular such that if the elbow pointed opposite the hand, they still went the direction the finger pointed.

Dogs and 2-year-old children tended to need to have the arm and hand protruding from the body to infer the direction of the hidden prize. Additionally, dogs and 2-year-olds were somewhat able understand that respond to pointing of the foot, but not as well as 3-year-olds. Finally, dogs consistently performed worse than 2-year-old kids, but in many cases, performed better than chance.

Well, that’s what the researchers concluded. But like all researchers I was skeptical. Seems like most of the time when I point to something the dog’s first response is to sniff my hand. So to see for myself, I decided to repeat the experiment on my own dogs. Surely two Jack Russells could perform as well as the average study dog.

To see the results, stay tuned for part 2 to appear in a few days.