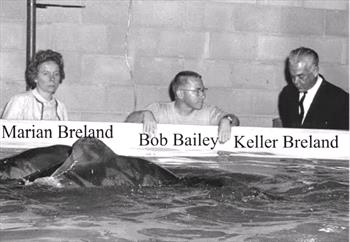

In the last blog, you learned about how and why Marian and Keller Breland started Animal Behavior Enterprises (ABE), the most successful and prolific animal training company that has ever existed. In this segment, you’ll find out more about Bob Bailey, how Keller got involved in developing the first scientifically trained dolphin show, and what dolphins were trained for in the Navy. Bob also reveals the four most common trainer errors.

Question:

Bob, how did you get into animal training?

Bob:

I was at UCLA. I was an Ich and Herps man while I was an undergraduate. I’d always been interested in behavior and watching animals. I was particularly interested in what they do to survive. So much of their survival depends on their behavior. They don’t just go out and suck their food in by osmosis. They go out and get it and that involves very intricate behavior. I’ve always been interested in evolution and the fact that behavior seldom leaves footprints. All we can do is speculate what behavior was like before based on what we know of the circumstances and the survival of the animal. Anyway, I started thinking up ways of conducting experiments. What could I do in the way of shaping this particular behavior?. Can these animals do these things? I’d had a few psychology courses, and I’d heard of Skinner and I had enough information where I could find books that I needed.

Question:

What types of experiments did you devise?

Bob:

I was feeding Congo eels in the lab and tested the effect of putting baby mice in different sections. Could I condition the eels to go to different places in this aquarium? By Jove, I could. They learned very quickly. When I’d walk in, the animal would anticipate and go to a particular corner. Well, I started to get more sophisticated and I’d move the plant around and always feed where the plant was. Pretty soon they’d go to wherever the plant was. That’s where I started really getting hooked. The first real experiment I did was working with a few of the tide pool fishes. I chose two varieties of one species that came in different colors: one was a reddish brown and one was a green with silver on it. I started studying first in the tide pools to see what kind of sea grass did you find them in. It turned out statistically significant relative to the color of the plant. I found that the fish would be found in plant of its color. So I asked what would happen if I created an environment with a matrix. I made four matrices: clear, black, green, and brown. I had eight aquaria and I studied the distribution in the eight tanks. I made the matrix out of clothes hangers and some plastic material like cellophane where the plastic was in the material but that the color didn’t leach out. The coloring was cut into strips that hung vertically like plants. There were hundreds of strips per area. Each day I’d walk in and observe using mirrors to see where the fish were and note what time. I let it sit that way for two days and then just rotate them 90 or 180 according to a plan. The fish hung out in the plant of the same color. Now, I didn’t know about controlling for light. I should have had yellow lighting or sunlight instead of fluorescent. So there were a lot of things I didn’t know about and didn’t care about. But I thought that was pretty neat because I could get them to move around very easily.

Question:

Bob, how did you become involved with the Brelands?

Bob:

In about 1962, I was chosen to be the Navy’s director of training. I really hadn’t had much formal training in animal training; however one of the few smart things [the Navy] did was hire Keller and Marian Breland of ABE. So they came out with some chickens and we spent a fair amount of time learning to train chickens. And I thought that was neat and I started applying that to training dolphins. Then our two dolphins died. When we captured them they were parasite infested and while we were getting new dolphins I went to Hot Springs, Arkansas, and spent a number of weeks there. There I was introduced to what animal behavior was all about. That is, changing behavior. At ABE they changed behavior and a lot of behavior. They changed lots of behavior in a short amount of time. Behavior analysis was the name of the game and that’s what they were calling it—behavior analysis. And that’s what they taught me to do.

I spent a little while with Keller to begin with. Keller was expansive, articulate. He could really articulate this stuff. Then I spent the rest of the time in an automatic trainer room. I got introduced to the monster—a bank of chickens in a box arranged four across and three down and you had to train all of them. You were shaping behavior of 12 chickens all at once. I found out what training was all about. You start out with one chicken. That’s not so bad. Two chickens gets interesting. Three chickens gets more interesting. At four chickens, the perspiration drips. Pretty soon you start being able to look and see pieces of behavior coming out. I got to about six. I was reasonable at six. That is the way to learn training. And, I loved it. To see your first few chickens coming out of the box and replacing them with new ones is great. I spent many months over the next three years in Hot Springs.

Question:

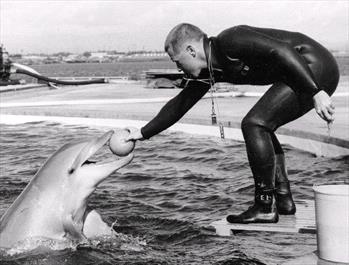

When the Navy finally got healthy dolphins what sort of missions did they train?

Bob:

For sea missions, normally the dolphin was launched from a helicopter or from a sea pen (they didn’t have special boats back then). Sometimes we used a high-speed boat if we were in a hurry but it was in the 1960’s. It’s different today and work has changed, but that’s how we started.

We’d have a large sea pen that housed the dolphin, a boat that we’d monitor from, and a target. The pen and boat are about one to two miles away and the target could be over six miles way. The dolphin would be guided in an erratic way instead of straight on and get to a target at the very end. So to go six miles the dolphin had to go much farther which meant that missions could last up to 12 hours. They would go through some terminal maneuver once they hit the target. Then they would guide the dolphin back to another pen. They used tracking systems, most of which are still classified. If the animals or humans screwed up, they had alternative sites and jobs to do. They didn’t want to lose the animal or abort the mission. There were other dolphins and schools of fish but the trained dolphins tended not to get distracted, although once, when we were working in Key West, a dolphin disappeared. It caught a grouper and came back and dumped it in the boat.

Question:

After the Navy, you went to work as a research assistant for ABE and later, a number of years after Keller passed away, became general manager. Can you tell me what made ABE different from other animal businesses?

Bob:

It’s right in the charter of ABE that the company was to demonstrate that there’s a better way, a scientific, technologic way of training animals and it need not use punishment. The real effort was to train animals in a humane way with less aversives, and to use the information that comes out of the laboratory. That was right in the charter. So the Brelands did that. When they began this in 1943, they believed that this technology was much more powerful than the scientists at the time thought it was. And not only that, within six months of the time they’d started their business, they realized that the key to high productivity was the use of the secondary reinforcer. Now they call it clicker training and the like. Regardless of what the secondary reinforcer was, they realized that precision training demanded a precision secondary reinforcer. So of all the people alive at the time, Skinner, notwithstanding, the Brelands were the ones to realize the technological impact of that one tool, the secondary reinforcer. And they really built their business on the secondary reinforcer.

Question:

Since you’ve found that the secondary reinforcer is such a powerful tool, are you a clicker purist?

Marian:

We’re not pure clicker trainers. We use the clicker when it’s advantageous. And appropriate and when it will do the most good. If you don’t know exactly what you want and you’re just waiting for the dog to do some behavior, you’d do a lot better to just chuck food. Just reinforce the dog. But if you want to establish precision, if you have a delicate point in the behavior that you want to emphasize, there’s nothing like the clicker. If you’re good on your timing, you can click the precise moment in the behavior that you want. There’s nothing like it.

Bob:

We deal in operant conditioning. I use positive reinforcement, I use negative reinforcement, I use positive punishment, and I use negative punishment. And the vast majority of all our training has been positive reinforcement. Between Marian and myself we probably have about 103 years of training experience. In the course of that, we’ve used positive punishment maybe a dozen times. So we stand pretty well on the side of you don’t have to use positive punishment except under really extreme, unusual situations. And certainly in pet training, there’s no reason I could see that you’d need to use an aversive for pet training, or, for that matter, obedience training in the ring.

Question:

How did you get started with chicken training camps for the public?

Bob:

We started in 1997 largely because of Terri Ryan and Karen Pryor and the like, who nudged us out of retirement back into training life. We had a lot of requests for chicken-training seminars and workshops.

Question:

In these workshops, what do you notice as the most frequent training errors?

Bob:

The number one error is that trainers are late on reinforcements or their reinforcement is ill timed. The next is the criteria — what you’re going to reinforce. One time they reinforce one thing and the next time they reinforce something else. Sometimes this is just poor decision-making and sometimes it’s just that people don’t recognize the behavior. They haven’t analyzed the behavior so they really don’t know what it is they want to reinforce. They just know what they want the final behavior to be. Thirdly, so many people are stingy with their rate of reinforcement. Also, trainers often don’t control the environment and the animal becomes distracted or afraid.

Question:

What encouragement would you offer to someone who wants to improve his or her training skills?

Bob:

Training is a mechanical skill. If you’re applying the proper techniques and your mechanical skill is good and you are following your timing, criteria and rate of reinforcement, you’ll get what you’re after.

Conclusion

So there it is, direct from the mouths of two of the greatest animal trainers who ever lived. I can only imagine what it was like to amass such a great knowledge from training so many animals and using scientific methodology for taking data, analyzing results and then making improvements in methodology quickly. The results: the ability to train dolphins for 12 hour missions in open ocean, to take six weeks to train what the best trainer took over two years to train and on your first shot, and the ability to train animals ranging from parakeets and pigeons to dogs, pigs, and sea lions all using the same principles. Unfortunately, most of the data collected at ABE burned in a fire and Bob’s knowledge can’t be downloaded into a computer. For now, I and a number of other trainers are trying to learn the most we from can from Bob since we will never have the opportunity to come close to what Bob, Marian and Keller at ABE did. And we strive to keep training a science so that we can continue to improve.

For more information on operant conditioning, read How to Behave So Your Dog Behaves.